The eight wars of religion (1562-1598)

In the 16th Century, France was to know a religious split : the great majority of the country remained faithful to Catholicism, whilst an important majority joined the Reformation. Coexistence of the two confessions throughout the Kingdom showed itself to be inapplicable. War could no longer be avoided and civil tolerance had failed.

Eight wars of religion were to succeed each other throughout 36 years, with periodic interruptions of fragile peace. The wars will cease with the Edict of Nantes (30th of April 1598), an edict that established a limited civil tolerance. The confessional duality established throughout France in 1598 was to wear away little by little until the revocation of the edict in 1685.

The 1st war (1562-1563)

On the 1st of March 1562, the Duke François de Guise massacred a hundred Protestants attending a service of worship in a barn in the town of Wassy. This event is considered to be the beginning of the first war of religion. Louis de Bourbon, prince of Condé, called upon the Protestants to take up arms. He captured the town of Orléans on the 2nd of April.

War spread throughout the kingdom. Both belligerents committed acts savage violence, especially the Protestant Baron des Adrets in the Dauphiné and in Provence, and the Catholic Blaise de Montluc in Guyenne.

In the battle of Dreux that opposed the troops of Condé and those of the High Constable of Montmorency, the royal troops had the advantage. The Duke de Guise laid siege to Orléans held by the Protestants (5th of February). He was assassinated by Poltron de Mere, one of the Amboise conspirators.

On the 19th of March the Amboise Edict of pacification was negotiated by Condé and the High Constable of Montmorency.

The 2nd war (1567-1568)

As from the autumn of 1567, the Huguenots leaders decided to take up arms once more. Worried by the increasing influence of the Cardinal of Lorraine on the young King Charles IX, they attempted to subtract the latter by forceful means from the Cardinal’s control. This attempt became known as the Meaux surprise. But the king was warned of it and outmanoeuvred it to return from Meaux to Paris under Swiss protection.

Several towns of southern France were taken over by the Protestants. Acts of violence are committed on both sides. In Nîmes, on St. Michael’s day – the 30th of September 1567 – the so-celled Michelade takes place : the massacre of leading Catholic citizens by Nîmes Protestants ; in Paris, besieged by the Huguenot army, Catholics violently attack Huguenots.

Condé’s army captured St. Denis and went as far as Dreux. But on the 10th of November 1567, the battle of St. Denis ends in favour of the royal troops, despite the fact that the High Constable Anne de Montmorency was fatally wounded.

After lengthy negotiations, on the 23rd of March, a peace treaty was signed : the Edict of Longjumeau that confirmed the Edict of Amboise.

The 3rd war (1568-1570)

The peace of Longjumeau lasted only five months.

The civil war in France was influenced by international events, especially by the revolt of the so-called “gueux” : subjects of Philip II of Spain in the Netherlands. Their cruel repression by the Duke of Albe in the name of Philip II caused great emotion in France and the Huguenots, seeking foreign alliances, concluded an agreement with them.

Furthermore, each of the two sides benefited from foreign aid :

- the Protestants were allied to the Prince of Orange and Elizabeth of England ; the latter financed the expedition in Burgundy of the Palatine Count Wolfgang, Duke of the Two Bridges, in 1569 ;

- the Catholics received help from the King of Spain, the Pope and the Duke of Tuscany.

Battles were fought mainly in districts of Poitou, Saintonge and Guyenne ; these resulted in two main victories for the Catholics : one at Jarnac (13th of March 1569) where the Duke of Anjou, the future Henri III, was victorious over the Prince of Condé who was killed during the battle ; and the other at Moncontour, in the northern district of Haut-Poitou (3rd of October 1569). Admiral de Coligny was injured during the battle but he managed to flee.

Despite these two setbacks, the Huguenots were not discouraged. Coligny returned north and reached La Charité-sur-Loire. In June 1570, the Protestant forces won the battle of Arnay-le-Duc.

The resulting peace indicated a political turn-about at the court where the moderates were recovering their influence while that of the de Guise decreased.

The edict signed at Saint-Germain on the 8th of August 1570, was brought about mainly by King Charles IX and marked a return to civil tolerance : freedom of worship was reinstalled in places where it had existed on the 1st of August 1570.

Protestants, moreover, obtained four strongholds for a period of two years : they were La Rochelle, Cognac, La Charité-sur-Loire and Montauban.

4th war (1572-1573)

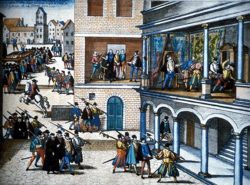

On the 22 of August 1572 – four days after the marriage of Henri de Navarre to Marguerite de Valois, sister of King Charles IX – Admiral de Coligny narrowly escaped an attempt on his life. In Paris the tension was very strong ; numerous Protestant noblemen had come to attend the wedding. During the night from the 23rd to the 24 of August – St. Bartholomew’s Day – the royal Council met, during which it was decided to eliminate the main Huguenot leaders. Coligny and other Protestant noblemen were assassinated at the Louvre as well as in town. This execution of a limited number of Huguenot leaders was followed by a savage massacre that will go on until the 29th of August with some 4000 victims. The massacre spread throughout country areas and resulted in some 10.000.

Henri de Navarre and the Prince de Condé were spared because of royal lineage, but were obliged to adhere to Catholicism.

The violence that had been unleashed against them forced many reformed Protestants to abjure or flee to the countries of the “Refuge” : Geneva, Switzerland, the northern provinces of the Netherlands or England. But in western and southern France battles raged once more. Nîmes and Montauban refused to accept the royal garrisons. La Rochelle was besieged but resisted. The siege was be lifted on the 6th of July 1573 and the King granted the Huguenots an edict of pacification : the Edict of Boulogne was registered by Parliament on the 11th of July 1573, but was less favourable than the preceding edict. The Protestants retain freedom of conscience but freedom of worship is granted to three towns only : La Rochelle, Nîmes and Montauban.

5th war (1574-1576)

The Duke of Alençon – the King’s young brother – took the lead of a movement made up of Protestant and moderate Catholics. This alliance of the “Malcontents” considered that tolerance towards reformed worship was primarily a matter of political reform. The movement stipulated demands for such reforms.

After the death of Charles IX (30th of May 1574), Henri III was crowned on the 13 of February 1575. He refused the Malcontents’ requests but was soon obliged to deal with them as his troops were far fewer than theirs. He signed a treaty of peace at Etigny, the so-called “peace of Monsieur”. The Edict of Beaulieu (6th of May 1576) confirms the victory of the Malcontents. It allows freedom of worship except in Paris and an area of two leagues (five miles) around the city. The reformed Protestants were attributed eight strongholds and limited chambers in every parliament.

6th war (1576-1577)

From the very beginning, the Edict of Beaulieu proved to be difficult to apply and raised opposition. Hostile Catholics gathered in defensive leagues. The States General was summoned and took place in Blois in an atmosphere that was most unfavourable to the Huguenots. Le assembly’s abolition of the edict resulted in the resumption of the conflict. But lack of financial aid for both parties obliged them to take up negotiations. A compromise was found and the peace of Bergerac (14th of September 1577 was confirmed by the Edict of Poitiers, signed in October 1577.

7th war (1579-1580)

War broke out once more in local areas : the Prince de Condé captured La Fère in Picardy and in April 1580, Henri de Navarre – at the head of the Protestant party since 1575-1576 – resisted the provocations of Lt. General de Guyenne and took possession of the town of Cahors. Some sporadic fighting occurred until the signing of the treaty of Fleix on the 26th of November 1580. This treaty confirmed the Poitiers text. As had been agreed upon at Poitiers, the strongholds were to be restored within six years.

8th war (1585-1598)

At the death in 1584 of François d’Alençon, Duke of Anjou and the King’s last brother, Henri de Navarre became the legitimate heir to the throne. In order to oppose this candidature to the throne, the Catholics constitute the League or “Holy Union”. Its leader Henri de Guise obliged Henri III to sign the treaty of Nemours (1585). The edict that followed was registered by Parliament on the 18th of July 1585, refuting the political status to civil tolerance. It stipulated that Calvinists had six months to choose between abjuration and exile, that ministers of religion be banned and that strongholds be given back.

The result was a strong decline in the number of Protestants throughout the country.

But Henri de Navarre, victorious at Coutras, still held the southern provinces.

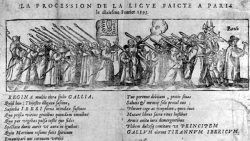

The League took control of northern France.

In Paris the “commons’” league had been constituted independently from the princes’ League. The two leagues now united.

On the 12th of May 1588, the city revolted : this was the “day of the barricades” and Henri III had to flee.

He took refuge in Blois and began negotiations with the leaguers. But the power acquired by the de Guise clan worried him. Suspecting subversion, he fought against it at all costs. He decided to have the Duke Henri de Guise and his brother the Cardinal of Lorraine assassinated.

Henri III sought reconciliation with Henri de Navarre. Their two armies joined forces and headed for Paris.

But the citizens of Paris rose against their King who had made alliance with the heretics. In 1589 Henri III was assassinated by a member of the League, the monk Jacques Clément.

Henri de Navarre became King Henri IV. But Paris was in the hands of the leaguers and the King had to conquer his kingdom.

In March 1590 the well-known battle of Ivry opened up the way for the King to the siege of Paris.

In 1593 Henri IV made known his intention to abjure and to undergo Catholic religious instruction. Only the anointing and crowning of the King in Chartres succeeded in overcoming Parisian reserve. Paris yielded in 1594 and opened up its doors to Henri IV.

In 1595 Henri IV received absolution from the Pope and declared war on Spain whose numerous troops that had helped the League were still present in France.

In 1598, by means of the Treaty of Vervins, he obtained the departure of the Spanish troops. Henri IV likewise obtained the submission of the Duke of Mercoeur, governor of Bretagnes, who had joined forces with the Spaniards.

The Edict of Nantes (30th of April 1598)

It was in Nantes, in April 1598, that Henri IV signed the well-known edict putting an end to the wars of religion that had ravaged France for some 36 years. This edict is more complete than the preceding ones. It established a limited civil tolerance and inaugurated religious coexistence. The Reformed service of worship was authorised in all placed where it existed in 1597 and access to all offices was guaranteed to Reformed Protestants.

Progress in the tour

Bibliography

- Books

- BOISSON Didier et DAUSSY Hugues, Les protestants dans la France moderne, Belin, Paris, 2006

- CHRISTIN Olivier, La Paix de religion : l’autonomisation de la raison politique au XVIe siècle, Le Seuil, Paris, 1997

- COTTRET Bernard, 1598, L’édit de Nantes, Perrin, Paris, 1997

- CROUZET Denis, Les Guerriers de Dieu. La violence au temps des troubles de religion, Champ Vallon, Seyssel, 1990

- GARRISSON Janine, Les Protestants au XVIe siècle, Fayard, Paris, 1988

- JOUANNA Arlette, La France du XVIe siècle, PUF, Paris, 1996

- JOUANNA Arlette, JBOUCHER Jacqueline, Histoire et dictionnaire des guerres de religion, Laffont (Bouquins), Paris, 1998, p. 1526

- LIVET G., Les Guerres de religion, PUF, Paris, 1993

- MIQUEL Pierre, Les Guerres de religion, Fayard, Paris, 1980

- PERNOT Michel, Les Guerres de religion en France, SEDES, Paris, 1987

- VRAY Nicole, La guerre des religions dans la France de l’Ouest : Poitou, Aunis, Saintonge, 1534-1610, Geste Editions, 1997

Associated tours

-

The eight wars of religion in detail

The wars lasted thirty-six years. The kingdom of France had 18 million inhabitants at that time – indeed, few other European countries had as many. The growth rate rose considerably... -

Wars of religion on the death of Henri IV (1562-1610)

In the 16th century in France, a war between the Protestant minority and the Catholic majority could not be avoided. In 36 years, between 1562 and 1598 there were 8...

Associated notes

-

The massacre of Wassy (1562)

From the protestant point of view the wars of religion began with the massacre of Wassy, whereas from the catholic point of view it was Louis de Condé’s attack on... -

The Edict of Nantes (1598)

This was Henri IV’s major achievement : the terms of this edict ensured the peaceful coexistence of Catholics and Protestants and brought a stop to all hostilities in France after 36 years... -

St. Bartholomew's Day (24th August 1572)

Charles IX had tried to reconcile the two religious parties, but when this failed, he was driven by the Guise family to authorize the Catholics to assassinate the Protestant leaders; the situation... -

Gaspard de Coligny (1519-1572)

Gaspard de Coligny born in the influential Châtillon family, was naturally at the service of the King of France. However, after being made prisoner at the siege of Saint Quentin,...