Religious Freedom

French Protestants were granted religious freedom during the Revolution.

Access to all employment, freedom of conscience and freedom of worship.

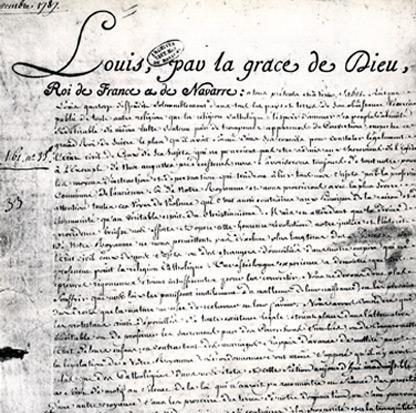

The Edict of Tolerance on 17th November 1787, had given back civil status to French Protestants.

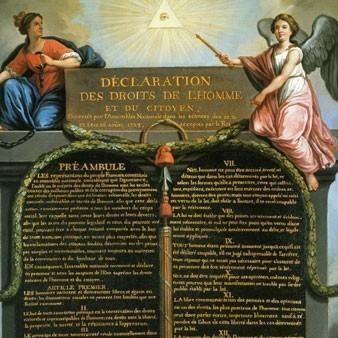

The Declaration of Human Rights on 26th August 1789, granted the Protestants freedom of conscience.

Article X of the Declaration of Human Rights, drafted by the Constituent Assembly, stipulates that “No one should be harassed because of his opinions, even in religious matters, as long as they do not disturb public order as defined by the law” (« Nul ne doit être inquiété pour ses opinions, même religieuses, pourvu que leur manifestation ne trouble pas l’ordre public établi par la loi »).

Whereas Louis XVI had granted non-Catholics the right to private worship in the Edict of Tolerance of 1791, the 1791 Constitution proclaimed each citizen free “to worship according to his beliefs” (“d’exercer le culte religieux auquel il est attaché”.)

Thus, by the end of 1791, the Revolution had met the common aspirations of Protestants.

Gradual resumption of Reformed worship

On 12th July 1790, the Constituent Assembly voted for the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which aimed to redefine the ecclesiastical map and reform religious worship, but it did not interfere with Protestant worship.

Religious meetings were gradually resumed almost everywhere, but links between churches were very slow to re-establish. In Paris, pastor Paul-Henri Marron led the first legal public worship.

After the Directoire (Board of Directors) had agreed, the Municipality rented Saint-Louis du Louvre church to a “body of people who professed the Protestant religion.” (une société de personnes professant la religion protestante”.) Thus, on 22nd May 1791, the Parisian Protestant community solemnly took possession of Saint-Louis du Louvre church and in it held their “first public service of Protestant worship”. (première assemblée publique du culte protestant”.)

« Scuffles » in Nîmes and Montauban

The Protestants were able to live peacefully, except for “scuffles” in Montauban on 10th May 1790 and in Nîmes on 15th June that same year.

However, these scuffles remained local events, although some were very violent and often bloody.

In general, these scuffles were thought to be motivated by politics rather than religion. There was rivalry between the Catholic aristocracy, wanting to keep local power and restore the influence of the Catholic faith, and the Protestant middle-class, who dominated economic activity and coveted political power.

In Nîmes, as in Montauban, supporters of the Old Regime managed to take over the municipality, but not command of the National Guard, and this was the source of bloody confrontations. The Protestants won in Nîmes, while in Montauban the Catholics were victorious. But the result was the same as both “aristocratic” municipalities were discharged by the Assembly.

Bibliography

- Books

- BOURDON Jean-François, Les pasteurs réformés face à la déchristianisation de l’An II, mémoire de maîtrise, Université Pierre Mendès-France, 1987

- VOVELLE Michel, La Révolution contre l’Église : de la raison à l’être suprême, Complexe, Bruxelles, 1988

- Articles

- "Les Protestants et la Révolution française", Bulletin de la SHPF, SHPF, Paris, 1989, Tome 127

- ENCREVÉ André, "Les Protestants et la révolution française", Réformes et Révolutions, VIALLANEIX Paul (dir.), Presses du Languedoc, Montpellier, 1990, p. 192

Associated tours

-

The Protestants under the French Revolution

In late 1791 in France the Revolution had answered the majority of Protestant expectations. Several Protestants were involved in the unfolding of events and took part in the different political...

Associated notes

-

The Edict of Toleration (November 29th, 1787)

With this Edict, King Louis XVI granted the Protestants civil status. He secured their right to live in the kingdom without discrimination for religious reasons. -

Paul-Henri Marron (1754-1832)

Paul-Henri Marron came from a Huguenot family which had sought refuge in the Low Countries. He was the first pastor of the Reformed Church in Paris. -

The French Revolution and the Protestants

In France, at the end of 1791, the Revolution had met the common aspirations of the Protestants.