Prophetic Movement

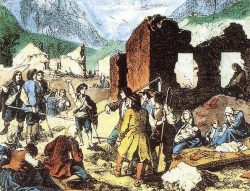

In the years following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, a Prophetic Movement, quite alien to the Reformed tradition, stirred up Protestant peasants from the South of France and led to the War of the Camisards (Guerre des Camisards).

The beginning of the Prophetic Movement

In 1688, a somewhat bizarre movement, new to Protestantism, arose in Dauphiné : Prophetism. Isabeau Vincent, a young shepherdess from Saou, near Crest (Drôme), talked in her sleep, first in dialect, then in French. She uttered a succession of verses or passages from the Bible, fitting the circumstances perfectly and following one after the other : “Stand firm – seek the Word, you will find it through repentance”.

People flocked to hear to her. She was soon arrested, jailed in Crest, and then held in a convent. But the movement of the “lesser prophets” did not stop ; in 1689 it spread to Vivarais. Speakers stirred up the crowds, indifferent to the consequences. The people were dealt with ruthlessly.

Prophetic expression

The majority of the prophets were young men and women from the country. Most were illiterate and could only speak dialect. Hence the surprise when people heard them prophesying in French, even if not quite correctly. This can be explained by their in-depth knowledge of Biblical texts, which were written in French, and an outstanding oral memory.

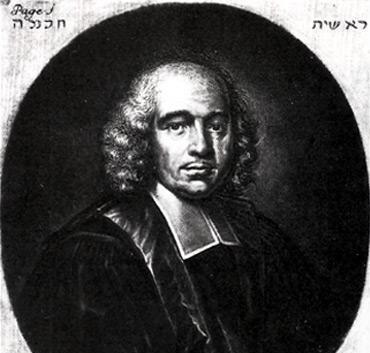

These prophets said : “Repent, no longer attend mass, renounce idolatry. Repent of the mass renunciation of 1685, stop pretending to be Roman Catholics, because the “fall of Babylon” (the end of the Roman Catholic Church) is near”. This prophecy stemmed from a text by Pierre Jurieu, published in 1686, “The fulfilment of prophecies”, which forecast liberation of the faithful within three years.

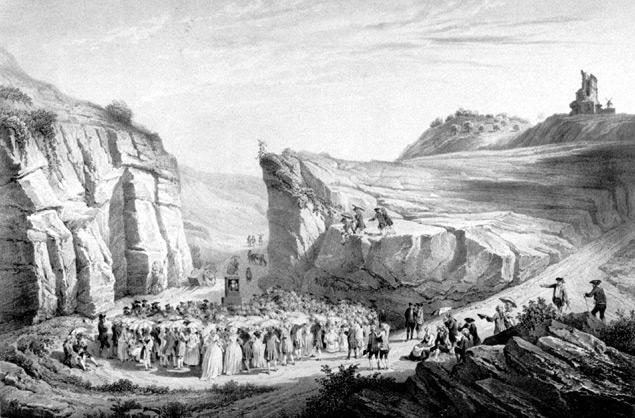

These passionate speeches were accompanied by extraordinary body movements : the prophets moaned, cried out, trembled, their bodies shook, they fell over and lay lifeless on the ground for several minutes. This shocking behaviour met with an almost general rejection.

Rejection by both Protestants and Roman Catholics

Both Catholics, and the Protestants from the Refuge, joined in rejecting them : “who are these common people who dare talk of religion ?” They were called impostors, fakers, comedians, lunatics, sick. At the Tour de Constance in Aigues- Mortes, where manypossessed womenwere jailed, the doctor sent by Intendant Basville, examined these “sick women” every day.

Some people spread the idea of a “prophet factory” where children would be taught to fake, to deceive. The prophets were called “dogs”, or “wolves” but more frequently “fanatics”. Except (notably) for Pierre Jurieu, ministers from the Refuge showed only contempt and disdain for these “lesser prophets”.

The War of the Camisards (Guerre des Camisards)

Ruthless persecution had silenced the “lesser prophets” from Vivarais, but, ten years later, following the death of Claude Brousson in 1698, and the disappearance of the last preachers, the movement had a resurgence, really catching hold in the Cevennes and Languedoc.

Prophet Abraham Mazel interpreted a dream of “two big black oxen eating all the cabbages in a garden” as a calling to sweep away the persecuting Roman Catholic clergy. The assassination of Abbé du Chayla triggered the War of the Camisards (Guerre des Camisards). It was a “holy” war, where the prophets played a major role : the rebels attacked or retreated, killed their opponents or let them live, as they felt led.

The end of the Prophetic Movement

After the end of the Guerre des Camisards, a few prophets remained active in the Cévennes.

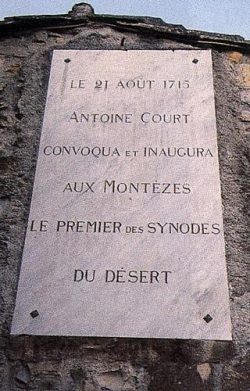

At the Montèzes Synod in 1715, Antoine Court reorganised the underground Reformed Churches and re-established order

The Camisard and prophet, Elie Marion, sought refuge in England, from where he attempted to spread the Prophetic Movement. He travelled across Europe, but failed to find support, except from some German Pietists

Progress in the tour

Bibliography

- Books

- CABANEL Patrick et JOUTARD Philippe, Les camisards et leur mémoire, 1702-2002, colloque du Pont-de-Montvert (25 et 26 juillet 2002), Presses du Languedoc, Montpellier, 2002, p. 278

- Articles

- CHABROL Jean-Paul, "Le prophétisme cévenol de 1685 à 1702", Bulletin de la SHPF, SHPF, Paris, 2002

- VIDAL Daniel, "De l’insurrection camisarde : une prophétie entrée en révolte", Les Camisards et leur mémoire, dir. CABANEL Patrick et JOUTARD Philippe, Presses du Languedoc, Montpellier, 2002

Associated tours

-

The Cévennes war

The « Cévennes war » was the name given in the 18th century to the guerrilla warfare that devastated the Cévennes in the early years of the century and tried... -

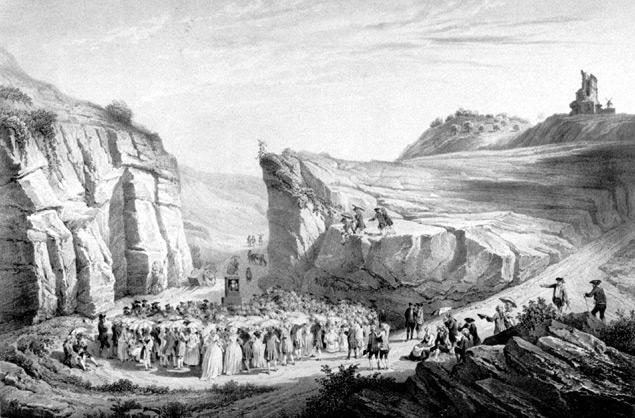

Religion in the “Desert” period

After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, French Protestants went into exile or abjured their religious faith. However, among those who abjured, some continued to practice in... -

The role of women in Protestantism

From the “good” woman of Proverbs to the woman citizen

Associated notes

-

Antoine Court (1695-1760)

Antoine Court gave himself to the restoration and reorganisation of Protestantism in France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685). -

Pierre Jurieu (1637-1713)

Pierre Jurieu was a pastor of the “refuge” and defended the rights of the people in the kingdom of Louis XIV. -

The secret meetings

Long before the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, freedom of worship for Protestants was already being questioned. Following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, three quarters...