Protestantism in 17th century

After the edict of Nantes and especially after the treaty of Alès, the protestant nobility declined in number. To a large extent, middle class businessmen replaced them as leaders of the reformed Churches.

The nobility

Prior to the treaty of Alès (1629), the ideals of the Protestantism were embodied by the protestant noblemen. But in the 17th century numbers declined considerably amongst the high nobility.

Amongst the provincial nobility, the Protestants remained faithful to their beliefs. In Picardy and in Burgundy, the local aristocrats used their feudal rights for the upkeep of the Churches.

Many members of the reformed faith became outstanding soldiers. Some served in the King’s army, others fought for his allies outside France.

After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, a number of Protestant military officers emigrated to join in the armies of William of Orange or the Great Elector of Brandenbourg.

The middle classes

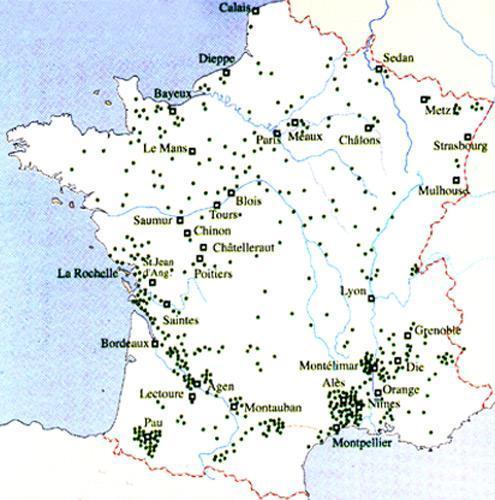

Protestantism had a greater following in towns than in rural areas.

From 1660 onwards, royal edicts progressively prevented Protestants from holding official positions. Many therefore turned to finance, business and craftsmanship.

Some outstanding public figures featured amongst the Parisian Protestants : for example, the banker Samuel Bernard or the businessmen of the Gobelin family.

In the provinces, amongst the Protestants featured silk manufacturers in Nîmes, merchants in Lyons and in Bordeaux, cloth manufacturers in Alençon and Montauban, paper manufacturers in Angoulême and tapestry makers in Aubusson.

Urban churches were well-endowed and their pastors well qualified.

Huguenots also featured in literary and artistic circles. One example is Valentin Conrart (1603-1675), the first secretary of the Académie française. Many Huguenot artists were members of the royal Academy of painting and sculpture.

The rural areas

In the Cévennes, the Bas-Languedoc and the southern part of the Poitou – regions where the Protestants had been a majority since the 1560’s – their numbers remained stable.

These rural Protestants lived in hamlets, villages or small towns and cultivated crops or bred sheep for their wool.

Bibliography

- Books

- LIGOU Daniel, Le protestantisme en France de 1598 à 1715, SEDES, Paris, 1968, p. 268

Associated notes

-

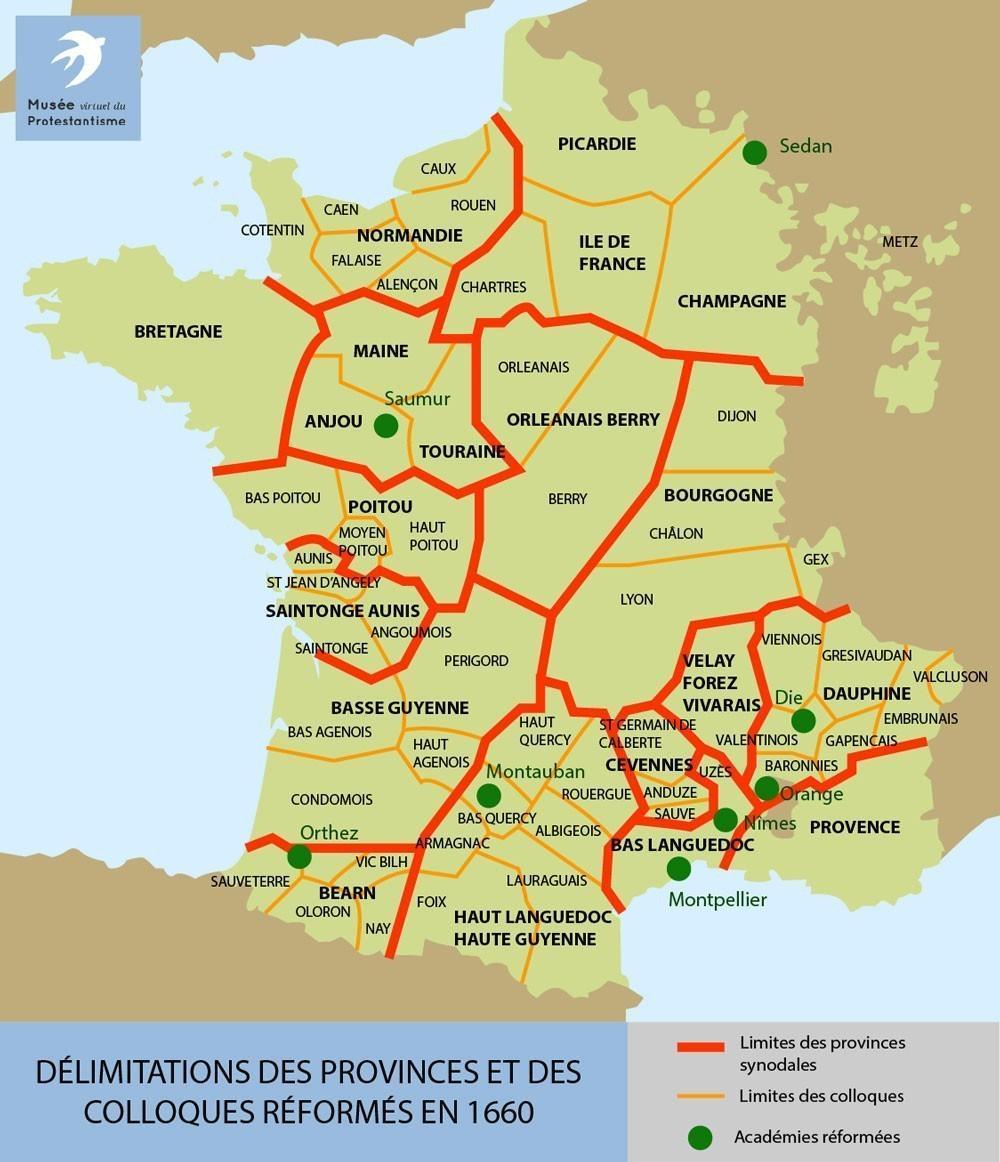

The sixteen synodal provinces (1660)

The Reformed Churches were grouped together according to the geographical framework of the kingdom’s provinces. Most reformed communities were based in urban areas, but there were also large rural groups... -

The geography of Protestantism (1660)

The reformed Protestants were found essentially in the provinces bordering the Atlantic as well as in the South of France, and not so much in the North of the country. -

The Lutherans in Paris

It is largely due to the kings of Sweden and their ambassadors as well as to the loyalty of the Swedish pastors, that the constitution of 1679 for the Lutheran... -

Protestant education in the 17th century

The basic aim of Protestant education in the 17th century was to hand on the Reformed faith. It was impossible, at the time, to imagine a non – religious education.