The reintegration

of Alsace-Lorraine after 1918

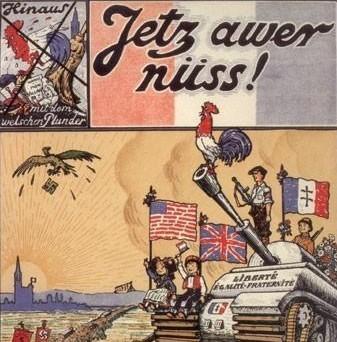

The return to France

If the reintegration of Alsace-Lorraine, now Alsace and Moselle, was not for the French in 1914 a primary cause of the war, revenge rapidly became one of the proclaimed objectives. The consensus was unanimous for the restitution of the provinces lost in 1871, and considered one of the conditions of peace for material, political and moral reasons ; as the Rev. L. Lafon said « the return of these regions to France has, for the civilised world, become the symbol of all obligatory reparations ». Protestants within France were happy to rediscover the protestantism of Alsace.

The arrival of the French troops was enthusiastically acclaimed. The « Vieux-Allemands » (« Old Germans »), about 100,000 people who had come from Germany, were expelled. Most Alsatian executives, considered pro-German, lost their jobs. « Sorting commissions » were set up to assess the situation of about thirty pastors, of whom ten were expelled to Germany.

The reorganisation of the Protestant churches and ecclesiastical authorities was no easy task. A board of direction was set up (later called council by the Lutherans, and a synodal commission by the Reformed. The government, fearing an excessive rise of pro-German elements intervened directly in certain nominations, enabling the pro-French to lead the churches. But many Protestants in Alsace were first and foremost Alsatians, neither French, nor German, which resulted in their being out of step with the new managers and this became a source of subsequent conflict.

Maintaining the faculty of theology within the secular university in Strasbourg also posed problems. The return of the theology faculty of Paris to Strasbourg, from where it had been transferred in 1871, was even evoked. Finally the status quo was maintained and the Rev. Paul Lobstein, a dogmatics professor in Strasbourg, successfully reorganised the faculty.

The Alsatian malaise

Squabbles soon emerged as 47 years of foreign rule had left their mark, and the Alsatian victims of the war were to be found in both camps, but mostly wearing the German uniform. Already some Protestant villages had been accused of being less enthusiastic towards the French troops than were the Catholic villages, and it must be said that the religious culture of the Protestants of Alsace was essentially Germanic. The « French of the interior », including the Alsatians who had settled in France after 1870, found it difficult to assess the profound modifications introduced between 1871 and 1914, notably the German system of decentralisation and the social protection, highly valued by the population. Parisian Jacobinism set up a series of laws for Alsace-Lorraine under the responsibility of a vice-secretary of state linked to the council presidency, and later to a general commission of the Republic. The organisation lasted until 1939, but the civil servants were not very conscious of the particularities of Alsace.

German became a foreign language, and Alsatian was considered a folk dialect. The population had a hard time adjusting to French legislation and was soon confronted with the economic and political problems of France. In 1924, E. Herriot the president of the council announced that he wished to introduce in Alsace-Lorraine, (still ruled by the Napoleon concordat) the 1905 French legislation on the separation of church and state. Opposition from Alsace was considerable and the government had to give up the project, but as B. Volger said « from the intermingling of languages, education and religious systems emerged the notion of self-rule ».

Public opinion was divided between the pro-French and French speaking “nationals” of urban, upper middle-class origin, and the complex group of “autonomists” comprising :

- a minority of separatists who wished to join Germany, or to become independent ;

- regionalists, the majority, valued the educational and religious status, and demanded decentralisation with administrative power ;

- true autonomists valued bilingualism, maintenance of the educational and religious status, but wanted decentralisation, not only administrative but also political.

Three political parties more or less encompassed these differences :

- The Republican Peoples’ Union (Union populaire et républicaine) recruited members (who often could not speak French) mostly in rural and working class populations. The movement, comprising mostly Catholics, was to become the Christian Democratic Party. They supported autonomy, and were in favour of introducing proportional representation and women’s right to vote.

- The Democratic Republican Party, the former liberal party, generally Protestant and urban, was regionalist, but nationalist and thus opposed to self-rule. Its leaders were Frédéric Eccard and the Rev. Charles Scheer.

- The Socialist party or SFIO with secular and Jacobin tendencies expanded, but communism remained marginal.

Whereas the 1920 elections had been overwhelmingly confessional, those of 1924 were marked by the growing influence of a desire for self-rule bringing together Protestants and Catholics.

A brilliant and forward looking solution to the general malaise was given by Charles Scheer, the Reformed pastor from Mulhouse who was elected representative from 1919 to 1928 on the « national block » list. His speech of 12 December 1921 « was so acclaimed as to be unanimously honoured, a rare phenomenon during a parliamentary career », (F.Eccart ). Charles Scheer declared « We do not accept accusations by the newspapers of neutralism, autonomism and federalism. One can have different opinions concerning the organisation of our country, but it is by no means a national matter. On the national level, we are all French… We need a movement of confidence…and also patience for Alsace to be and to remain French… Alsace is French. Have faith in Alsace ! »

The Protestants of Alsace and the churches of the interior

The Protestant churches of the interior (or homeland) quickly made contact with those of Alsace-Lorraine. But once the enthusiasm of the first meetings had waned, the differences in church organisation raised problems, as the Alsace-Lorraine churches were still under the concordat regime.

The French Protestant Federation, founded in 1905, was a place for meetings and discussions, and the Reformed Church of Alsace-Lorraine immediately joined. For the Lutherans (ECAAL) to come closer was more difficult, « brotherly relations, but no direct membership » ; The Lutherans of Alsace did not wish to alter either their religious practice, (the use of Luther’s Bible and German hymns) or their relation to the state. They also feared the emergence of trends which they considered “sectarian” within the Federation.

But the Reformed Church of Alsace-Lorraine and the Catholic church of Alsace- Lorraine progressively extended their collaboration with the churches of France through the Protestant Federation ; they remained sensitive concerning their independence but felt the need to create links and to widen their horizons. The ecumenical movement and its various meetings were significant factors for bringing them closer.

The choice of Strasbourg for the general assembly of French Protestantism in 1924, testified to the desire to iron out problems. In 1924, seven out of the twenty-eight members of the Council of the French Protestant Federation represented Alsace-Lorraine, but none of them was a member of the board.

Bibliography

- Books

- STORNE-SENGEL Catherine, Les protestants d’Alsace-Lorraine de 1919 à 1939 : entre les deux règnes, Collection Recherches et Documents, Société savante d'Alsace, 2003, Tome 71, p. 371

Associated tours

-

Protestants in Alsace since 1871

Few French provinces have experienced as many traumatic experiences as Alsace, twice annexed to the German Reich and twice returned to France. The Protestant community participated, with varying degrees of...

Associated notes

-

Charles Scheer (1871-1936)

The life of this Reformed pastor from Mulhouse was marked by his political commitment as a Francophile and by his role in the ecumenical movement. -

Alsace from 1945 to the present

The Liberation (November 1944 to March 1945) – reinstated the legality of the French Republic and the particularities of Alsace were affirmed, such as the worship concordat, school statutes, and... -

Alsace from 1871 to 1918

The annexation of Alsace and of the Moselle part of Lorraine to the 2nd Reich, (Treaty of Frankfurt, 10 May 1871) was a terrible shock to the population who believed... -

François Wendel (1905-1972)

François Wendel was a lutheran lawyer who devoted much study to the Reformation movement, religious institutions in Alsace and Calvin. He was appointed Dean to the protestant University of Strasbourg,... -

Alsace and World War II

The declaration of war led to the evacuation of one third of the population of Alsace : from Strasbourg and the border cities to the south-west of France, and the University...